In 1784, Thomas Jefferson replaced Benjamin Franklin as United States minister to the court of King Louis XVI. Upon Jefferson’s arrival in Paris, Franklin promptly updated the Virginian on the latest political and diplomatic news from Versailles. Dr. Franklin also updated Jefferson on the latest wine vintages and introduced him to the best wine merchants in the city.

Jefferson’s five years in Paris radically changed his life. Though Parisian hotel culture was unpalatable, many of its aspects nevertheless captivated Jefferson. Its intellectual atmosphere stimulated Jefferson’s mind, while its culinary novelties delighted his taste buds. As Jefferson’s diplomatic talents burgeoned, so did his understanding of the European palette.

Jefferson’s five years in Paris radically changed his life. Though Parisian hotel culture was unpalatable, many of its aspects nevertheless captivated Jefferson. Its intellectual atmosphere stimulated Jefferson’s mind, while its culinary novelties delighted his taste buds. As Jefferson’s diplomatic talents burgeoned, so did his understanding of the European palette.

Nowhere was this more apparent than on his famous southern tour, his “peep only into Elysium” in the spring of 1787. Jefferson’s grand tour of 1787 took him from cold, damp Paris through picturesque Burgundy, down the Rhone Valley and into Marseilles. Traveling alone, Jefferson mingled with local peasants and aristocrats alike, absorbing the local flavors of each stop. He stated that he “courted the society of gardeners, vignerons, coopers, farmers, etc. and have devoted every moment of every day almost, to the business of enquiry” He marveled at France’s Roman antiquities, declaring the Pont du Gard, “sublime,” and finding inspiration for the Virginia State Capitol building in the Maison Carrée at Nîmes.

Most importantly he savored the finest Chateau wines in the world and studiously recorded their production methods. Stopping in Burgundy, Jefferson marveled at the 11th Century wine presses that were still in use by the monks at the monastery, Chateau du Clos de Vougeot. In Meursault, he visited the source of his favored white table wine, Goutte d’or, and commented how the red Burgundy soil appeared almost identical in color and texture to the red loam of his native Albemarle County.

Farther south, traveling down the Rhone River Valley he tasted the brilliant, but little known wines of l’Hermitage. Jefferson later deemed white Hermitage “the first wine in the world without a single exception” and served it at the White House.

Continuing through Italy he discovered still more new wines and methods of planting vines. Of the Italian Riviera, Jefferson noted, “… if any person wished to retire from their acquaintance, to live absolutely unknown, and yet in the midst of physical enjoyments, it should be in some of the little villages of this coast…” On one occasion in northern Italy, under penalty of death, he smuggled out a few handfuls of rice grains in the husk. Jefferson sent the grains to the South Carolina Society for Promoting Agriculture, where it was determined that they were in fact inferior to the variety farmed in South Carolina.

In Bordeaux, Jefferson walked through the vines at Chateau Haut-Brion, just as his philosophical hero, John Locke, had done one hundred years before. Overwhelmed with excitement, he immediately shipped six dozen bottles of Chateau Haut-Brion to his brother-in-law, Francis Eppes, stating, “I can not deny myself the pleasure of asking you to participate of a parcel of wine I have been chusing for myself… it will furnish you a specimen of what is the very best Bordeaux wine.”

In Bordeaux, Jefferson walked through the vines at Chateau Haut-Brion, just as his philosophical hero, John Locke, had done one hundred years before. Overwhelmed with excitement, he immediately shipped six dozen bottles of Chateau Haut-Brion to his brother-in-law, Francis Eppes, stating, “I can not deny myself the pleasure of asking you to participate of a parcel of wine I have been chusing for myself… it will furnish you a specimen of what is the very best Bordeaux wine.”

Upon his return to America, Thomas Jefferson would order his wines directly from the proprietors whom he had met on his tour, ensuring that he received only the finest vintages, bottled at the chateaux, at great financial expense.

Throughout his European travels, Jefferson indulged in a cornucopia of culinary delights that he and his colonial counterparts had never experienced. In Italy, he tasted pasta and promptly charged his secretary to acquire a “Maccaroni mould.” In Holland he dined on waffles, and in France he savored delicate sauces and rich desserts. Upon his return to America, visitors to Monticello and the White House were treated to a taste of Americas first “Nouvelle Cuisine.”

While traversing Europe, Jefferson ordered wine from many different dealers and chateaux and had his shipments sent to both Paris and America.

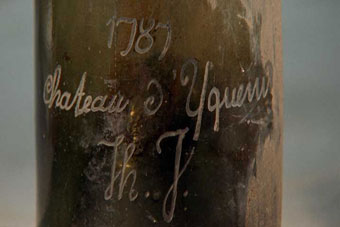

In 1985, a German wine connoisseur and collector was consigned about a dozen bottles of what appeared to be eighteenth century Bordeaux wines bearing etchings of Jefferson’s initials. Reminiscent of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, these bottles were said to be found bricked behind a cellar wall in France. It is assumed that the owner of the house intended to save the bottles from the French Revolution. The wines were later auctioned off; and one bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite brought $157,500. At a tasting of the purchased wines, one connoisseur concluded that Jefferson’s wine tasted of peaches and cream. Much controversy has surrounded these “Jefferson” bottles with many historians labeling them as frauds, while others convinced they are authentic.

In 1985, a German wine connoisseur and collector was consigned about a dozen bottles of what appeared to be eighteenth century Bordeaux wines bearing etchings of Jefferson’s initials. Reminiscent of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, these bottles were said to be found bricked behind a cellar wall in France. It is assumed that the owner of the house intended to save the bottles from the French Revolution. The wines were later auctioned off; and one bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite brought $157,500. At a tasting of the purchased wines, one connoisseur concluded that Jefferson’s wine tasted of peaches and cream. Much controversy has surrounded these “Jefferson” bottles with many historians labeling them as frauds, while others convinced they are authentic.

During his diplomatic tenure, Jefferson sampled the finest wines at many of the grandest tables in Europe. More importantly, he established personal relationships in the wine industry that would serve him well after his return to America. By that time, he possessed a depth of knowledge and an appreciation of wines that was unparalleled by anyone in the young country.