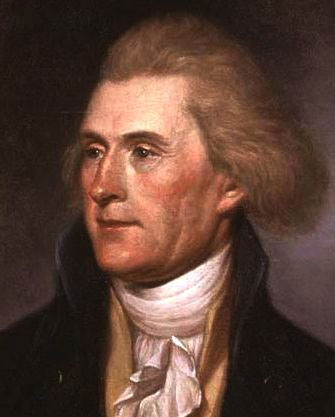

When nominated to be the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson listed his profession as “farmer.” Although he spent most of his life in the political arena, Jefferson always considered himself a man of agriculture. His accomplishments as a founding father and politician have been well documented. However, his struggles as a vintner and his passion for the finest wines have remained relatively unexplored.

Over the course of his life, Jefferson’s love for wine never waned, stating simply “Good wine is a daily necessity to me.” In his experimental garden, Jefferson raised a number of domestic and exotic fruits and vegetables, but throughout his life, he was most enthusiastic about the cultivation of the wine grape not only at Monticello, but also throughout the United States. Jefferson’s immersion in the subject of wine enveloped him to such an extent that all but six lines of his lengthy congratulatory letter to James Monroe on his election to the presidency dealt with those wines most suitable for public entertaining.

Over the course of his life, Jefferson’s love for wine never waned, stating simply “Good wine is a daily necessity to me.” In his experimental garden, Jefferson raised a number of domestic and exotic fruits and vegetables, but throughout his life, he was most enthusiastic about the cultivation of the wine grape not only at Monticello, but also throughout the United States. Jefferson’s immersion in the subject of wine enveloped him to such an extent that all but six lines of his lengthy congratulatory letter to James Monroe on his election to the presidency dealt with those wines most suitable for public entertaining.

Jefferson held the belief that wine was the most civil of drinks. Compared to the strong Ports and Madeiras, crude ales, and hard spirits consumed by his peers, wine in his words remained, “the true restorative cordial.” The ever-optimistic Jefferson believed that the delicacy of fine wine, like knowledge, could uplift man’s spirit and refine his soul. He even went so far as to affirm, “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap; and none sober, where the dearness of wine substitutes ardent spirits as the common beverage.” To this end, Jefferson endeavored to reform the taste of his new nation, using his Renaissance palate to guide America away from its rather bland English culinary heritage.

Jefferson’s initial interest in wine can be partly attributed to the friendship with his mentor, prominent Virginian George Wythe. While studying law in Williamsburg, Jefferson undoubtedly sampled some of the best European wines at Wythe’s table. Later, as a young revolutionary, Thomas Jefferson hired his own personal vintner, Phillipo Mazzei, to oversee the planting of vineyards at Monticello.

Jefferson’s passion for wine was inflamed during his five-year mission in France serving as United States Minister to the court of King Louis XVI. While in France, Parisian hotel culture excited Jefferson’s interests in art, literature, politics, architecture, science and, undoubtedly, wine. While feasting at France’s finest tables, Jefferson was exposed to the upper echelon of the world’s finest wines. The spectacular Burgundies and Bordeaux inspired the ever-curious Jefferson to explore the sources of these incredible vintages. In the winter of 1787, Jefferson embarked on a trip that he described as “instruction, amusement, and abstraction from business…” And it is no coincidence that he visited France’s most prestigious wine regions and vineyards. In addition to traveling through the lush wine country of France, he also journeyed to Northern Italy, where his palate was overwhelmed by its fresh, flavorful wines and extraordinary cuisine.

Jefferson’s passion for wine was inflamed during his five-year mission in France serving as United States Minister to the court of King Louis XVI. While in France, Parisian hotel culture excited Jefferson’s interests in art, literature, politics, architecture, science and, undoubtedly, wine. While feasting at France’s finest tables, Jefferson was exposed to the upper echelon of the world’s finest wines. The spectacular Burgundies and Bordeaux inspired the ever-curious Jefferson to explore the sources of these incredible vintages. In the winter of 1787, Jefferson embarked on a trip that he described as “instruction, amusement, and abstraction from business…” And it is no coincidence that he visited France’s most prestigious wine regions and vineyards. In addition to traveling through the lush wine country of France, he also journeyed to Northern Italy, where his palate was overwhelmed by its fresh, flavorful wines and extraordinary cuisine.

Upon his return to the United States, Jefferson promptly adopted many of the culinary and agricultural traditions he had observed in Europe. Most importantly Thomas Jefferson became a powerful advocate of European wine making techniques. He envisioned, “We could in the United States make as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe, not exactly the same kinds, but doubtless as good.”

During his distinguished national political career as Secretary of State, Vice President and President, Jefferson spent a significant percentage of his salary importing the best wines from Europe.

After retiring from public service in 1809, Jefferson retreated to his mountain estate, Monticello. There he again attempted the cultivation of European wine grapes, though he later concluded that native vines were the key to the future of American wine. Jefferson spent the next 17 years entertaining prominent guests, pursuing his varied interests, and indulging his passion for wine. Although retired, Jefferson still retained one lasting duty as a public servant – he remained wine consultant to future presidents until his death in 1826.

Thomas Jefferson fostered the winemaking efforts of other Americans, and he experimented relentlessly on his own. A pattern of renewal and failure marked the vine-growing efforts at Monticello, and it seems most appropriate to perceive his viticultural pursuits as experimental, his approach optimistically scientific, and his vineyard a vital part of the Monticello laboratory. Jefferson’s lack of success can be attributed to his long absences from Monticello, the inevitable attacks of insects, fungus and disease, and perhaps simple neglect. Despite Jefferson’s shortcomings as a vintner, his efforts, patronage, and passion for wine have not been matched in the United States.